Picture this: a death is reported to authorities, but they find only 1 bone, can’t interview anyone about what happened, and have no fancy diagnostic tools to evaluate DNA left at the scene.

That’s what fawn survival researchers are usually up against.

At a fawn mortality site, there is often not enough evidence to uncover what contributed to the fawn’s death. Predators may gobble up any evidence of disease or malnutrition before investigators can even get there. And I can assure you, those predators aren’t talking to us to confess their involvement in the crime or whether they were just an innocent passerby.

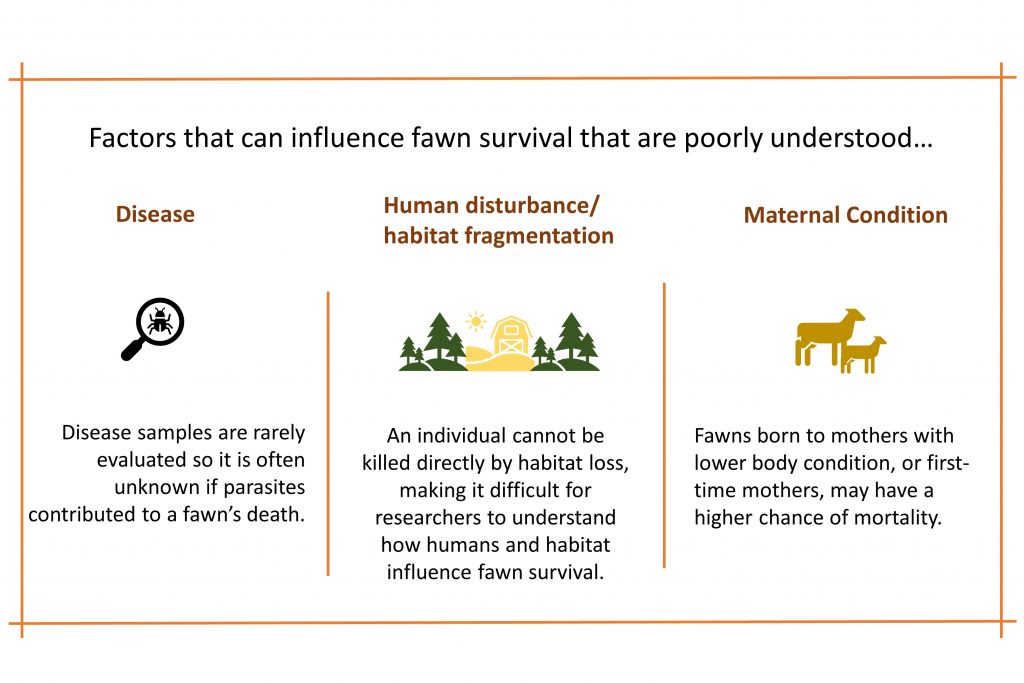

When there is just a carcass, the evidence that is available can cover up what really happened. Bite marks are easier to see than parasites. Bear poop with fawn hair in it doesn’t tell you that his meal was skin and bones to begin with. Moreover, disease samples are rarely evaluated because they are expensive. And DNA isn’t a slam dunk in identifying the killer.

If you’ve ever seen a murder mystery, you know that there are often red herrings at the beginning leading investigators and viewers to think they know who’s guilty. But, alas! At the last minute a scrap of evidence points to the REAL killer.

Right now, predators are often the red herring. Study after study has found predators to be main source of fawn mortality. But almost no studies look at fawn survival outside of predation. What if we are missing something? Researchers need evidence to determine what made a fawn susceptible to mortality in the first place.

So, that’s what we did. We looked at fawn susceptibility to mortality before a fawn died. No mortality site mysteries and no evidence covered up by bite marks and poop.

How did we do this? Hormones.

Cortisol is a hormone released by mammals (yes, humans have it too!) when they are stressed. Hence the term “stress hormone.” Researchers often measure cortisol concentrations in wild species to understand what things in the environment stress them out.

In adult deer and elk, salivary cortisol has been used to understand how populations and individuals respond to hunting pressure, habitat variation, and environmental conditions like weather. We know that high levels of the stress hormone may be harmful to an individual’s health, but no study of wild ungulates has ever linked it to survival.

Cortisol can be good or bad. Helping to make stored energy quickly available, cortisol can help fawns respond quickly to stressors. Running from a predator, for example, is stressful and requires a quick burst of energy and cortisol helps make that happen.

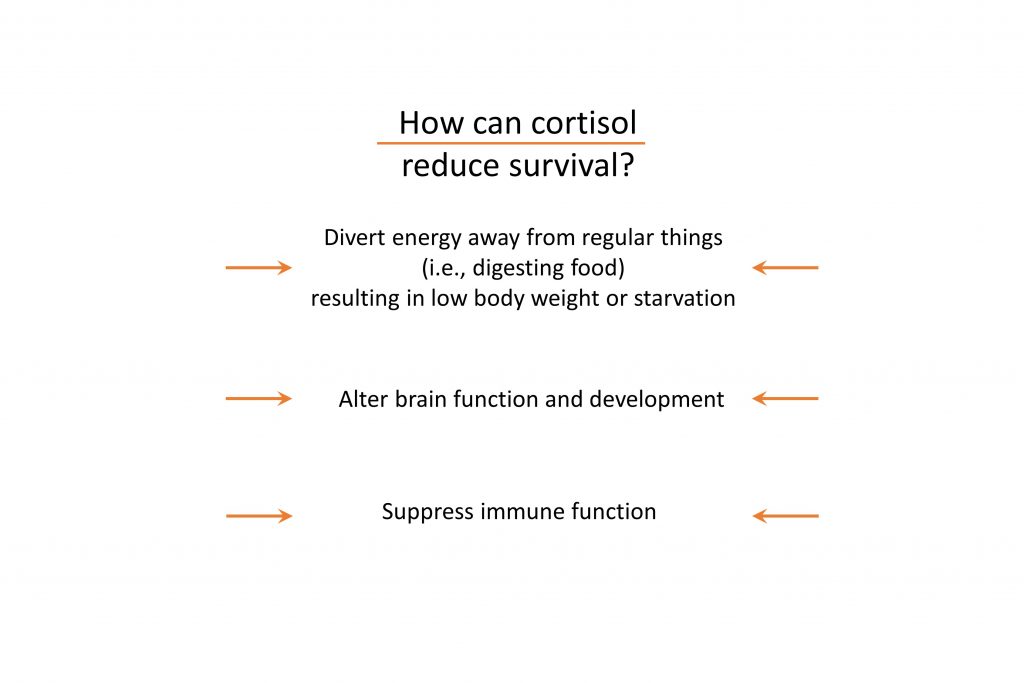

When cortisol is released into the body for a long time, however, it can have negative effects. Being prepared and ready all the time means energy is being diverted to behaviors that keep fawns on high alert instead of using it for normal body functions. Studies of many mammal species show that food digestion, immune system support, and general growth of the body and brain are all negatively influenced by long-term cortisol release.

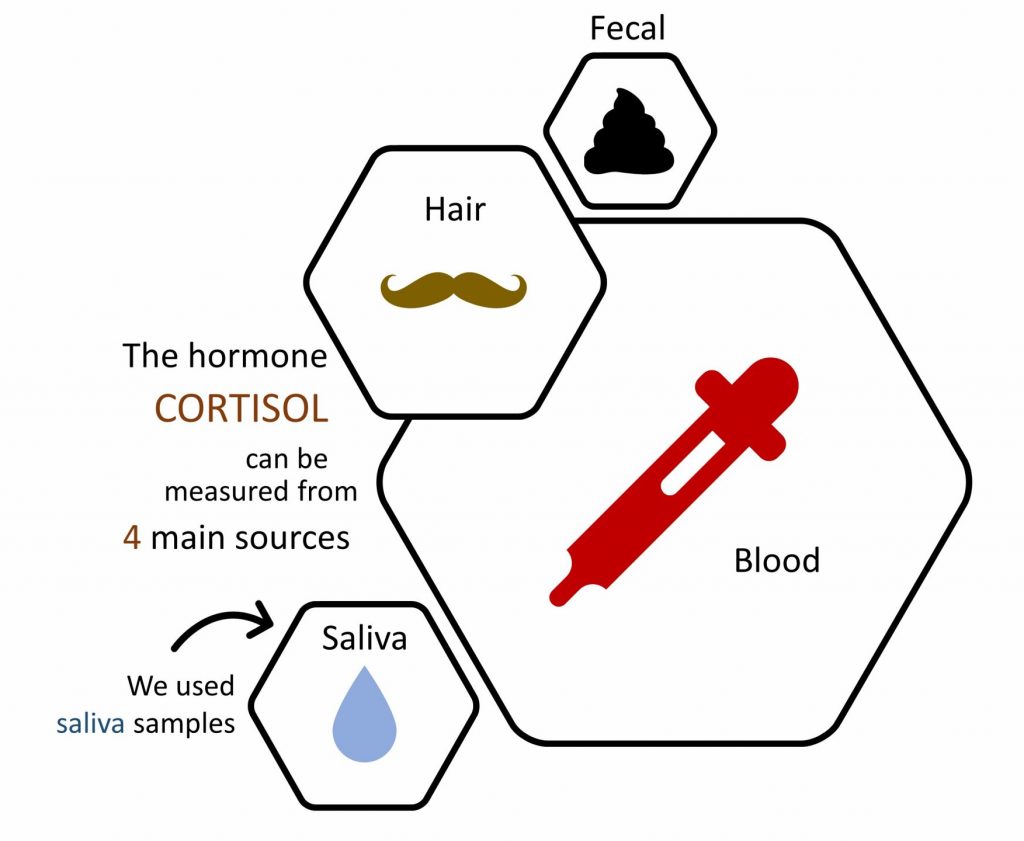

To look at fawn cortisol levels and link them to survival, we sopped up fawn spit during the capture event and then scurried back to our lab. The amount of cortisol in the saliva told us how much of this stress hormone each fawn’s body was exposed to each day.

Since there is a lot of evidence that suggests cortisol can be bad for an individual’s survival, body condition, brain development, and immune system, we hypothesized that high cortisol concentrations would be bad for fawn survival too.

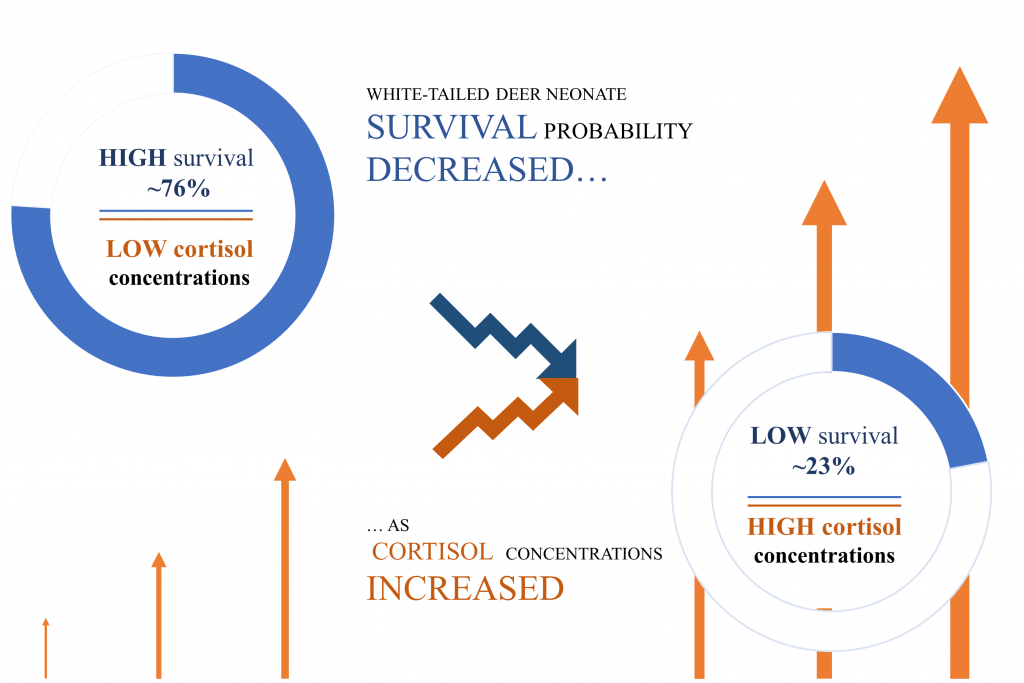

And guess what! Fawns who had higher cortisol concentrations in their saliva had lower survival.

An important distinction is that we don’t know if the high cortisol concentrations CAUSED higher mortality or not. It could be that fawns with higher cortisol levels experienced stressful conditions that caused mortality. For example, a fawn may be starving, which can elevate stress hormone levels, and the lack of food kills the fawn rather than the elevated stress hormone levels.

What’s important is that hormones may be a way to evaluate things in the environment that affect fawns but are difficult to evaluate when just looking at a carcass. Because predators are the most detected mortality source in North America, it is often hypothesized that fawn stress would be greatest in areas where predators are abundant. But that isn’t what we observed. When we looked at two study areas, fawns from a study area with fewer predators and lower predation rates had the higher stress levels.

What could be stressing fawns out if not predators? Momzillas. The study area where fawns were more stressed had more young mothers in the population. Young mothers can be less successful at rearing fawns. Maternal condition also influences offspring condition, potentially leaving fawns stressed and malnourished. As a result, it’s possible that these factors elevated fawn stress more than predators. This is all speculative, however, because very little is known about how maternal condition influences fawn stress or survival.

With this being the first study of its kind, more research is needed to evaluate links between cortisol and survival in other populations. Spit may be the evidence that helps better understand what influences fawn mortality! The plot thickens as it does in every murder mystery.

One thing is very clear- fawn researchers need more evidence.

Recently, a study from Delaware showed that only 54% of fawns survived even when there were no predators around. The culprit? Disease. Often overlooked and difficult to quantify, disease may contribute to fawn mortality by directly killing fawns or making them more susceptible to other mortality sources. It was likely easier for the Delaware study to detect disease because predators weren’t there to cover up any evidence.

Pairing our results with the Delaware study, it’s clear that mortality events don’t give us the whole picture on fawn survival.

Disease and hormones are only two of the many poorly understood factors that can affect fawn mortality. It’s high time we stop blaming those passersby predators for every death in the woods.

-Tess Gingery

Research Associate

The Deer-Forest Study