Fawning season is fast approaching and babies of all shapes, sizes and persuasions (deer aren’t the only ones proliferating) will be everywhere before you know it.

Reproduction is important to understanding population dynamics which can play a part in management. It’s one of the many reasons we did 2 fawn studies in the last 25 years. These studies are expensive because they requires lots of people on the ground searching for fawns. Let’s review some of the methods that can be used to assess pregnancy and catch fawns:

- Venture into the forest pretending to be a fawn by bleat calling and waiting for mom to respond.

- Capture adult, female deer after the breeding season, fit her with a GPS collar and VIT, and wait for the technology to signal us that a birth has occurred.

- Capture an adult, female deer after the breeding season and take a blood sample to analyze for pregnancy hormones. However, this only tells us a doe is pregnant; not if a fawn was born.

All these methods (and more) have been used to determine if and when does will be dropping fawns.

What if we could tell whether a doe has given birth by how she is moving on the landscape? The Deer-Forest Study has deployed lots of GPS collars on adult females and tracked their movements. One of the many benefits of a long-term project are these little sidebars that can be investigated.

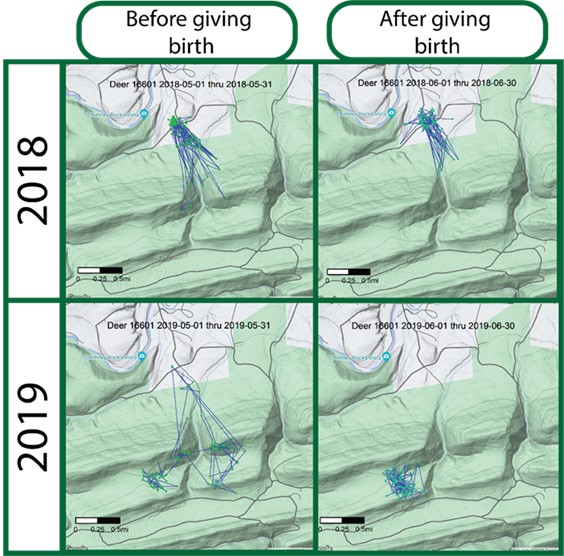

We’ve seen some does abandon their normal stomping ground and head to a new location to give birth. Others constrict their movements to a smaller area. It can be easy to recognize when a does leaves her established home range during the fawning season. Shifts in movement behaviors, such as how far they are moving and if they are taking many or no turns, can also be seen in GPS locations.

Katie Gundermann, a graduate student at Penn State, looked to see if birthing events could be reliably detected in deer just from GPS information alone. Katie took the GPS locations of does that were confirmed to have given birth and applied two statistical models (one to detect a geographic change in location and one to detect a change in movement metrics). The models were successful in detecting when a birthing event occurred in Pennsylvania’s other ungulate (elk), but when it came to deer, the models could not consistently determine a birthing event.

I feel like I can hear them laughing – “Oh you think your fancy model can tell you when I go into labor and deliver, well think again.” Some deer may make predictable movements around birthing events, but most does included in this study did not make movements that followed the patterns in the models.

Knowing when many females are giving birth can make finding those little buggers more efficient but we aren’t going to be able to do that with GPS collars.

-Jeannine Fleegle with Katie Gundermann

Wildlife Biologist

PA Game Commission