I have a reminder set on my phone for the first of every month. It simply says, “Dog pills.” My aging companion is on several daily prescriptions which I religiously give her to improve the quality of both our lives. But it’s her once-a-month heart worm and flea & ticks pills that always slip my mind. These improve quality AND safety of our lives.

Flea and tick control is standard for most pet owners. The spectrum of issues they cause range from physical irritation (I swell up just thinking about ticks) to dangerous health issues (my girl has tested positive for several “osis” at the vet).

But we are the lucky ones. There are many options available to me for controlling those little bloodsuckers. Not so for wildlife. And now that summer is here, they are all awake and hungry.

Ticks are ranked second as vectors of human diseases worldwide with mosquitoes reigning supreme. But they are the most important vector of disease-causing pathogens in domestic and wild animals. Lyme disease is, of course, the most well-known tick-borne disease but it didn’t become part of the mainstream until the 1980s. Since then the list has expanded. Tick-borne disease in the US include anaplasmosis, babesiosis, bourbon virus, Colorado tick fever, ehrlichiosis, Heartland virus, Powassan disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, STARI, tickborne relapsing fever, tularemia, 364D rickettsiosis, and Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis. And it just keeps getting longer.

If you want to strike fear into the heart of every meat-eating hunter, alpha-gal syndrome (AGS) will do the trick. AGS is a condition that produces an allergic reaction after exposure to or consumption of red meat. All this triggered by the bite of a tick.

It’s no wonder why controlling ticks is topic of research. A study recently published looked at low-dose fipronil deer feed. Fipronil is a broad-spectrum insecticide and is the active ingredient in topical Frontline with which you may be familiar. However, there have been applications of oral fipronil in cattle and more recently dogs.

Could feeding deer a dose of insecticide-spiked grain similar to the monthly pill I give my dog reduce tick burden?

Unsurprisingly, feeding deer fipronil killed ticks that decided to take a bite. Two different treatments (48-hours of fipronol feed and 120-hours of fipronil feed) produced 90% reduced female survivorship of black-legged ticks (Ixodes scapularis) and 80% reduced female survivorship in lone star ticks (Amblyomma americanum). The effect wore off over time like the pill I give my dog. For deer, the concentration of fipronil in blood plasma was related to tick survivorship. As it decreased, so did tick mortality. Tissues samples were also collected from treated deer and tested for fipronil. Concentrations of fipronil in muscle, fat, and liver all decreased over time (taking 22-56 days to reach levels lower than EPA maximum residue limits).

Black-legged tick (Ixodes scapularis)

Photo: Jim Gathany

This is very interesting. However, the paper suggests the next step is a field trial with wild deer. Putting aside the logistics of a field study to evaluate the effect of fipronil laced feed on the tick burden of wild deer, we need to talk about this in a larger context.

Lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum)

Photo: Jim Gathany

Me treating my 4-legged fur baby with tick-killing chemicals has a measurable effect on disease for her. But that does not mean fewer tick-borne diseases in me. Reducing tick abundance does not translate into fewer cases of tick-borne disease in humans. Logic suggests fewer ticks equals fewer cases of Lyme disease or babesiosis or anaplasmosis, but it does not.

Even if killing ticks meant less Lyme et al (which it doesn’t), how large an area would we need to treat? How many feeding stations would need to be set up? How would we control dosage? What about all the other critters that might find fipronil feed tasty? Free-ranging deer are…well…free-ranging – beholden to no human, free to come and go as they please, and eat what and as much as they like. Broad scale application of a pesticide has never gotten us into trouble before, right?

And the elephant in the room is feeding deer itself. Feeding wildlife is bad. I won’t get into it here, but I am PASSIONATE about this. Feeding promotes habituation, transmits disease, and alters behavior. Deer do not need our assistance and if they do, it’s because we have screwed something else up.

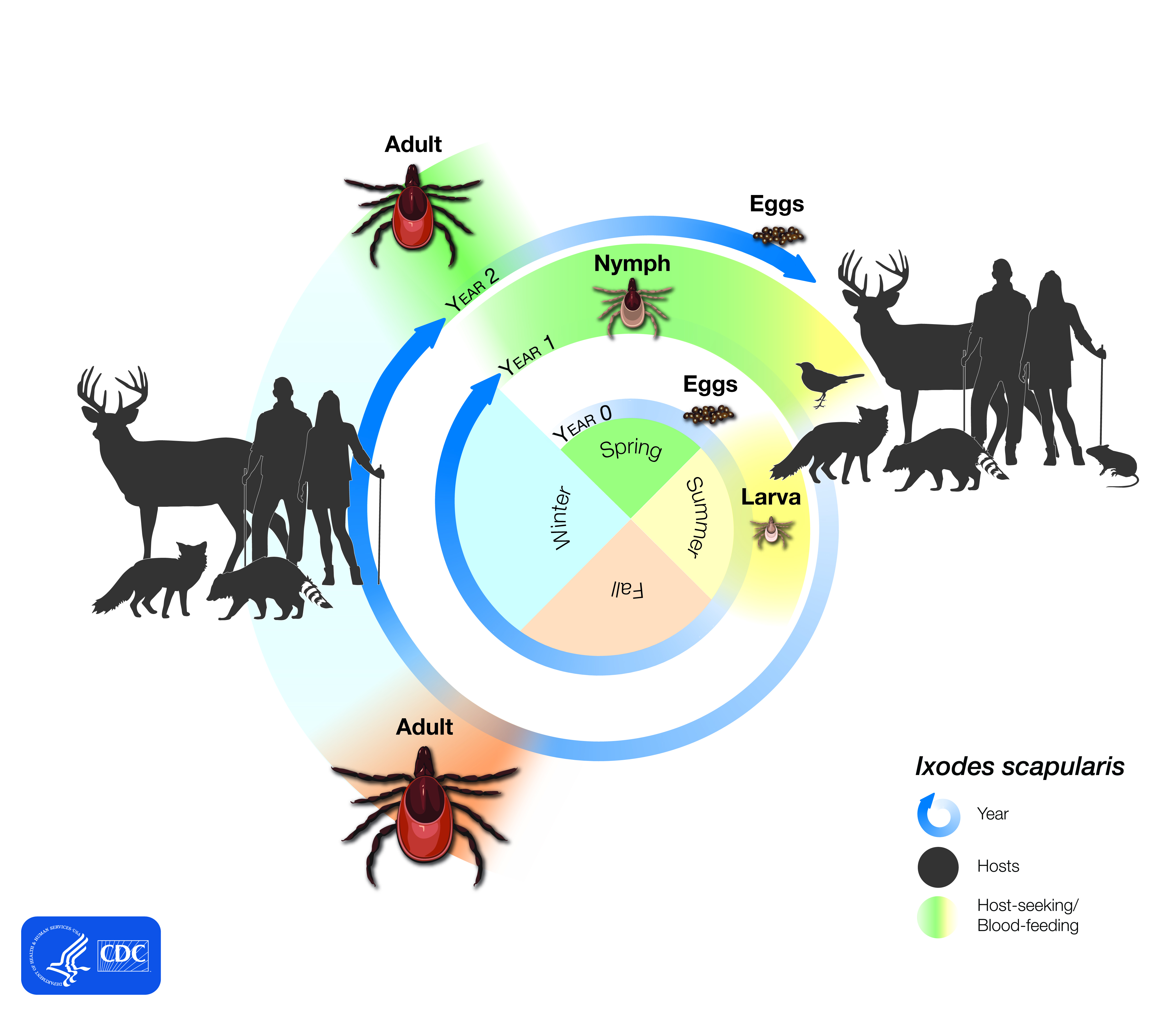

Climate change has brought the rise of the tick. Geographic range expansion as well as increased abundance is double trouble. And tick-borne diseases are clearly a public health threat. But let’s make sure we keep the baby and not the bathwater. Solely focusing on tick reduction on a single species or area is likely not the answer. Natural systems are complex and dynamic. Ticks, themselves, have a 2–3-year life cycle. Before we go tugging on another string, let’s ask a few more questions.

-Jeannine Fleegle

Wildlife Biologist

PA Game Commission