Now that you have been sufficiently advised about the content of this post (and you are still reading), I am assuming you are not young or sensitive. If you are, STOP. TURN BACK NOW.

Ok, that makes 2 very clear warnings about this post. If you continue on and have complaints, take them elsewhere.

What in the world could sanction such notices of potentially offending content?

VAGINAL IMPLANT TRANSMITTERS.

Yes, you read that correctly. And yes, it is exactly what it sounds like.

We are placing transmitters in a doe’s vaginal tract.

This is our second year using VITs and, as a colleague noted during this year’s training, the guilt isn’t any less the second time around.

Let’s put aside the logistics of deploying these transmitters and talk a bit about the technology.

This is a VIT (with a magnet taped to the side that keeps it switched off until deployed). The design is based on hormone implants for livestock developed to increase pregnancy rates and exactly time the birthing period for a herd of animals (the VITs we use do not contain any hormones). VITs have been tested and found to be safe for deer.

The VIT is equipped with a temperature sensor. When it is warm and happy, it beeps (a radio signal) slowly to save battery power. When the temperature changes or drops, the signal speeds up making it easier to locate.

Each VIT is also paired with a GPS collar. When the temperature sensor in the VIT changes, the collar then sends an email message to the researcher.

The VIT/collar pair will also alert us if the VIT and collar are separated regardless of temperature.

If everything works as it is designed, it is quite amazing and invaluable in finding newborn fawns on a challenging landscape.

This is all well and good. This is also where things stop being G-rated.

Now to the task of deploying these marvels of modern field science.

This is the dangerous end of a deer.

It is to be respected and approached with caution. A deer’s hind quarters can propel them 20 mph and 8 feet into the air.

You don’t want to be on the receiving end of a kick. Power is one thing but those delicate looking hooves are razor sharp and can slice through any kind of clothing or skin.

We will be working with this end of the deer. The doe is sedated, of course, to make handling safer for all parties involved.

This is the applicator. That’s correct, it is simply 3/4″ PVC.

The VIT is placed inside the applicator (3/4″ PVC) and a length of 1/2″ PVC serves as a plunger to expel the VIT once the applicator is in place.

And this is where the applicator and VIT are going.

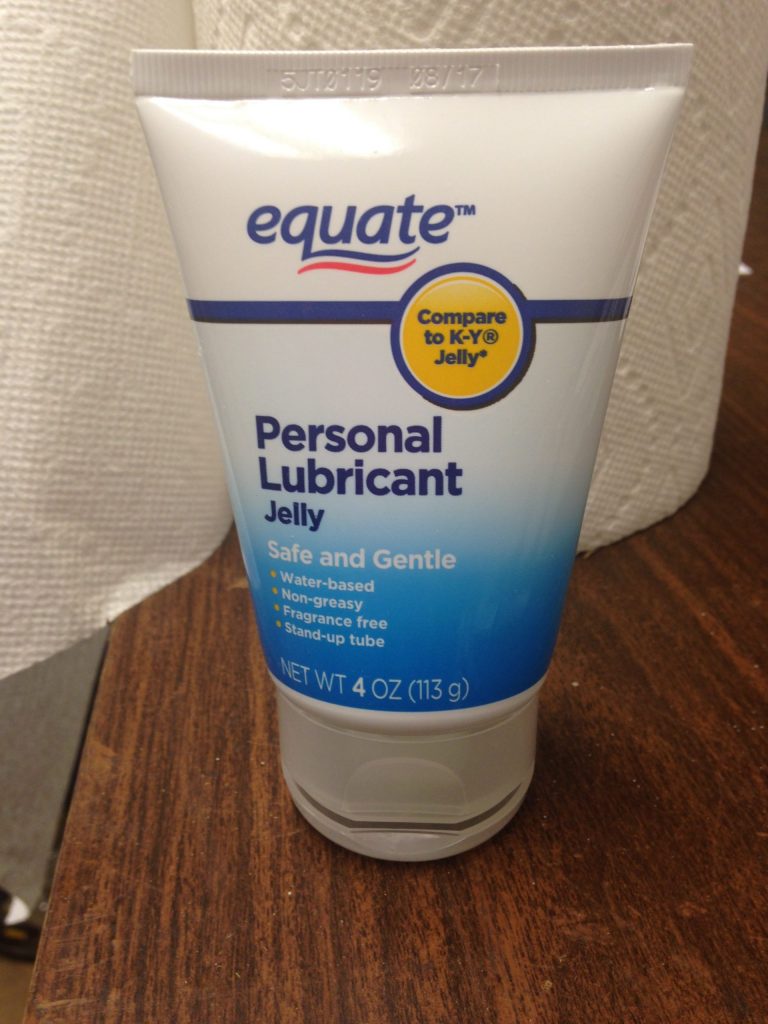

But there is some prep work that needs to occur first. The vulva is lubed and probed.

The doe is understandably “tense.” Things need to relax a little in order to get the applicator where it has to go.

Once things are judiciously lubed and as relaxed as a sedated wild animal having her private parts probed can be, it’s time to insert the applicator.

And slide it in until it reaches the cervix.

Once there, the applicator is slowly removed but the plunger is held in place (to expel the VIT and keep it in place against the cervix).

Look closely, you can see the antenna!

The procedure is complete.

But we aren’t done. All does with VITs also have a GPS collar (remember the pairing) and ear tags.

When we are done, she comes to with all kinds of stuff on and IN her. See what I mean about the guilt? Granted these animals aren’t harmed but they are surely inconvenienced (perhaps this is a bit of an understatement).

The value of these deer increases exponentially when the reversal drug is administered and they are released. They are sporting thousands of dollars in equipment. But that’s not the real value. Add up the days it took to capture her, the hours to check on her collar after she is tagged, the data being collected, the potential capture of 1 or both of her fawns, which in turn will be tagged and collared – she is in fact invaluable to the research project. For without her, there would be no research project.

So I guess that justifies (kind of) the means to an end…but I doubt this unwilling patient would agree.

-Jeannine Fleegle, biologist

PGC Deer and Elk Section

We like to have some fun with the blog posts, but handling deer is serious business. The protocols we use follow guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists. In addition, the training our crews received is reviewed and approved for the safety of the field techs and the deer. The bottom line is that studying wildlife is a balance between the safety of the animal and the need for data. Most importantly, we want our procedures to have as little effect on the behavior and physical well-being of the deer, because we need the study deer to be representative of the population.