Spiderman’s ability to sense impending disaster is uncanny. It is believed that this predictive power is shared by the white-tailed deer with regards to a looming winter storm. Granted, white-tailed deer don’t have superhuman strength and web shooters. But if they could sense oncoming storms, they could use it to their advantage by increasing food intake and finding shelter before the storm hit. That would be a pretty awesome power!

If white-tailed deer can predict a storm, is it a learned behavior or something more instinctive with a genetic basis perhaps influencing survival rates?

In the Centre County region of Pennsylvania, winters are characterized by temperatures of 10.4°- 39.2°F with average wind speeds of 4.9 miles per hour and snowfall of 45 inches per year. Winter storms occur with the passing of a cold front. These fronts are associated with a drop in barometric pressure, colder temperatures, high winds, and precipitation. Does this make that Spidey sense tingle?

In the winter months, white-tailed deer minimize energy expenditure and actually lose weight. One way to minimize energy loss is to decrease overall movement in addition to physiological changes.

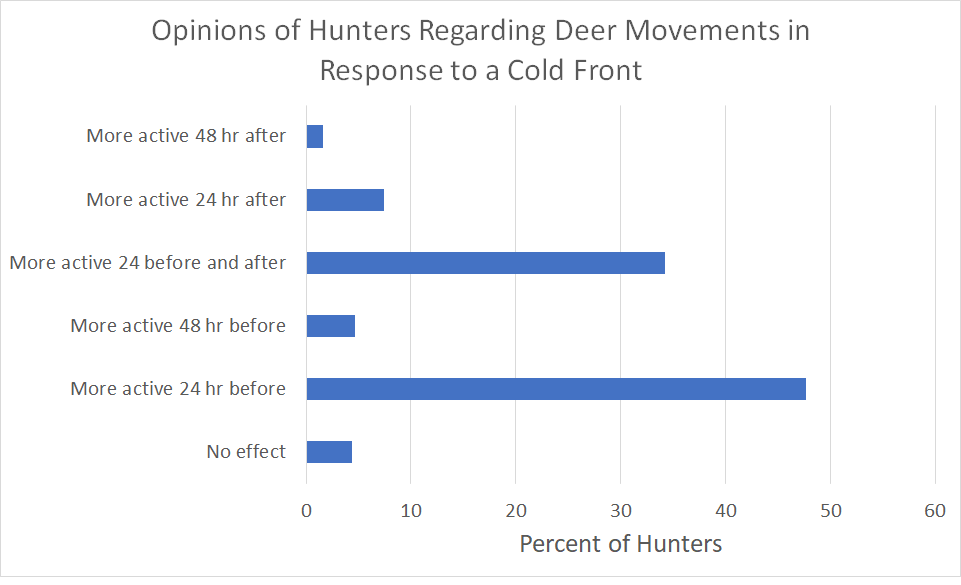

Conventional wisdom is that deer are more likely to feed before the onset of a winter storm. According to a poll of our readership (n = 1,668), 48% of respondents said that deer are more active 24 hours before a cold front arrives and 34% of individuals stated that deer are more active 24 hours before and after a cold front arrives.

My prediction was similar to popular opinion. If deer have a Spidey sense, they should increase movement 24 hours before onset of a winter storm, decrease during the storm, and then increase for 24 hours after the storm.

To test this, I identified winter storm events and analyzed hourly locations of adult female deer (> 2 years old) fitted with GPS satellite collars from January through April 2015–2017. Identification of a winter storm cold front is based on the wind shifting from S-SW to W-NW, increasing wind speeds, temperature drops, and a sudden rise in barometric pressure after a drop. Local weather data were used to spot these patterns.

Thirty storm patterns and 52,279 GPS locations from 4 deer in 2016 and 8 deer in 2017 were used to measure Spidey sense.

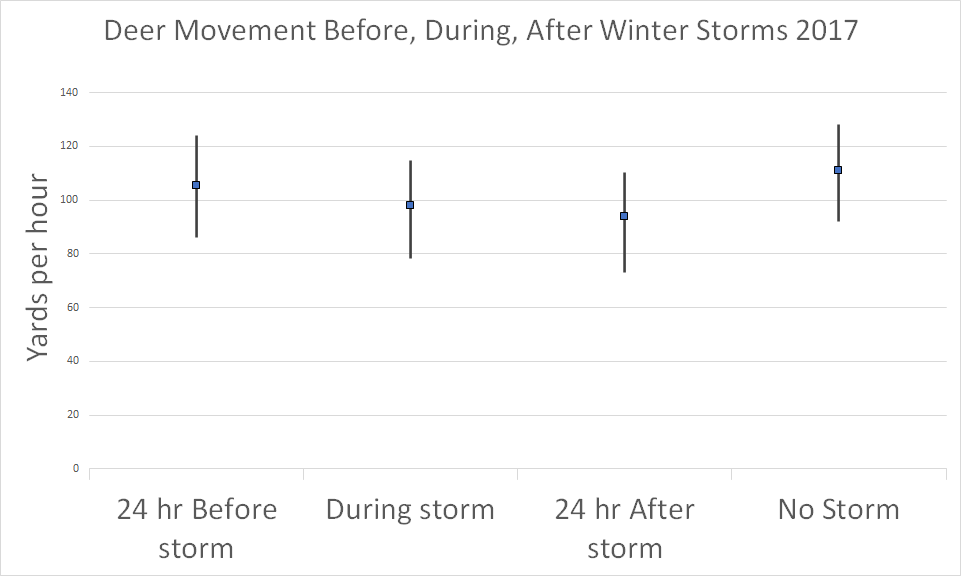

Distance each deer moved per hour were calculated and hours denoting time periods that were before, during, or after a storm were identified. I then tested whether the mean speed differed 24 hours before, during, and 24 hours after a storm while comparing them to periods where no storm was present.

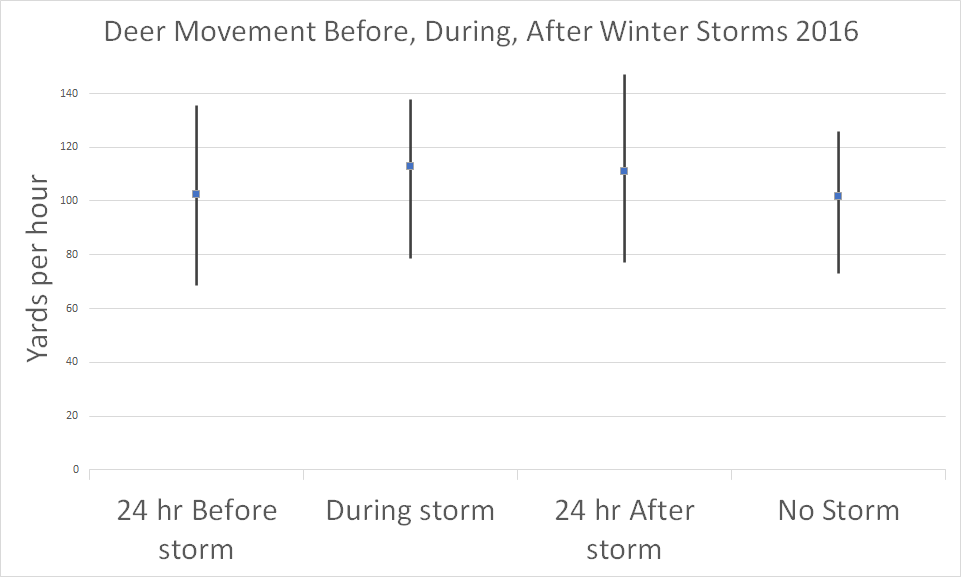

In 2016, average speed was 105 yds/hr – speed Before a storm was approximately 102 yds/hr, During = 113 yds/hr, After = 111 yds/hr; No storm =102 yds/hr.

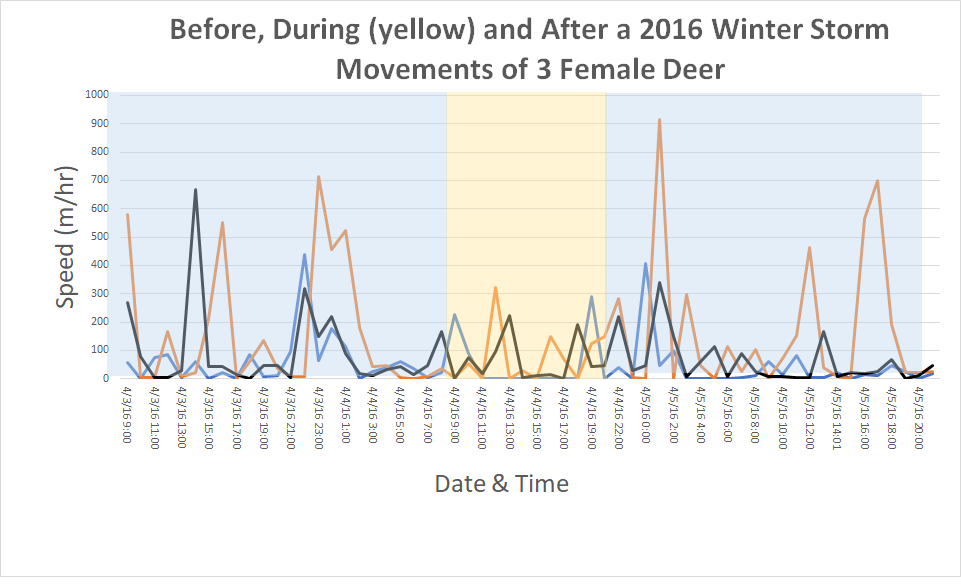

In 2017, average speed was 102 yds/hr – speed before a storm was approximately 105 yds/hr, during = 98 yds/hr, after = 94 yds/hr; No storm = 111 yds/hr. Looking at the movements of individual deer in 2016, a clear pattern is not evident. The graphs below are for 2016 of 3 deer during a single storm event. The next graph has point estimates (with 95% confidence intervals) of mean speed before, during, after, and no storm.

Although there are spikes of increased activity before a storm, there is no significant evidence to suggest that movement consistently increases before a storm event (light blue frame on left). In fact, speed before a storm is similar to no storm. Deer do display reductions in movement during a storm and possibly after as well (yellow frame in middle).

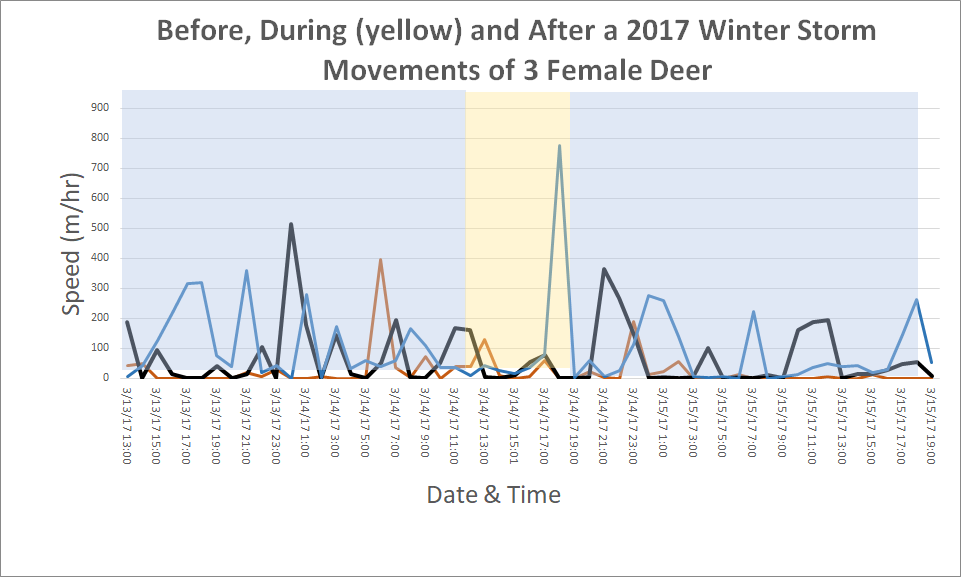

Results for 2017 are consistent with that of 2016. Interesting to note that Deer 17168 (blue line) shows a spike in movement during a storm. Again, estimates of mean speed show similar activity rates before a storm and when no storm is present.

Data show no statistical or biological significance of oncoming winter storms on behavior or movement of our collared deer.

Alas, it appears deer do not have a Spidey sense. White-tailed deer do have a bunch of other cool characteristics that probably do fall under “superhero” status but predicting oncoming winter storms just isn’t one of them.

–Dana Arnold

Class of 2021

Wildlife and Fisheries Science

If you would like to receive email alerts of new blog posts, subscribe here.

And Follow us on Twitter @WTDresearch