I look forward to spring every year. Daffodils, peepers, and promise of summer with some 60 degree days. To that end, 2025 has been a bust. The daffodils and peeper held up their end of the bargain just to be slapped by weeks of cold, rainy, gross weather. I’ve been depressed

But last night an unexpected rise in temperature lifted my spirits on my evening walk and prodded others out of their slumber. I spotted a couple of bats feasting on a recent hatch of insects. YES!! Signs of life! Lots of critters besides bats and bugs check out in the winter only to reemerge during more favorable conditions, including snails.

One of our very first blog posts was about snails and the possible interaction of soil and vegetation and deer. Ten years later, I’m going to talk about snails and deer and…”worms.” Specifically, nematodes. A parasitic bug if you will. Technically, neither worms nor nematodes are bugs. And I’m positive entomologists, helminthologists, and nematologists would be highly insulted, but this is my blog post.

For those keeping count, this is my third “bug” related post in as many weeks. This one was Duane’s idea. Parelaphostrongylus tenuis is a parasitic roundworm that infects many hooved mammals but white-tailed deer are their natural host. Also known as brain worm or meningeal worm, they are affectionately called P. tenuis by those that study them (or students that take courses in which spelling counts).

Bug or not, P. tenuis has a complicated and fascinating life cycle. Several life stages and different host animals are required to complete a full transition from an egg to an adult that lays more eggs.

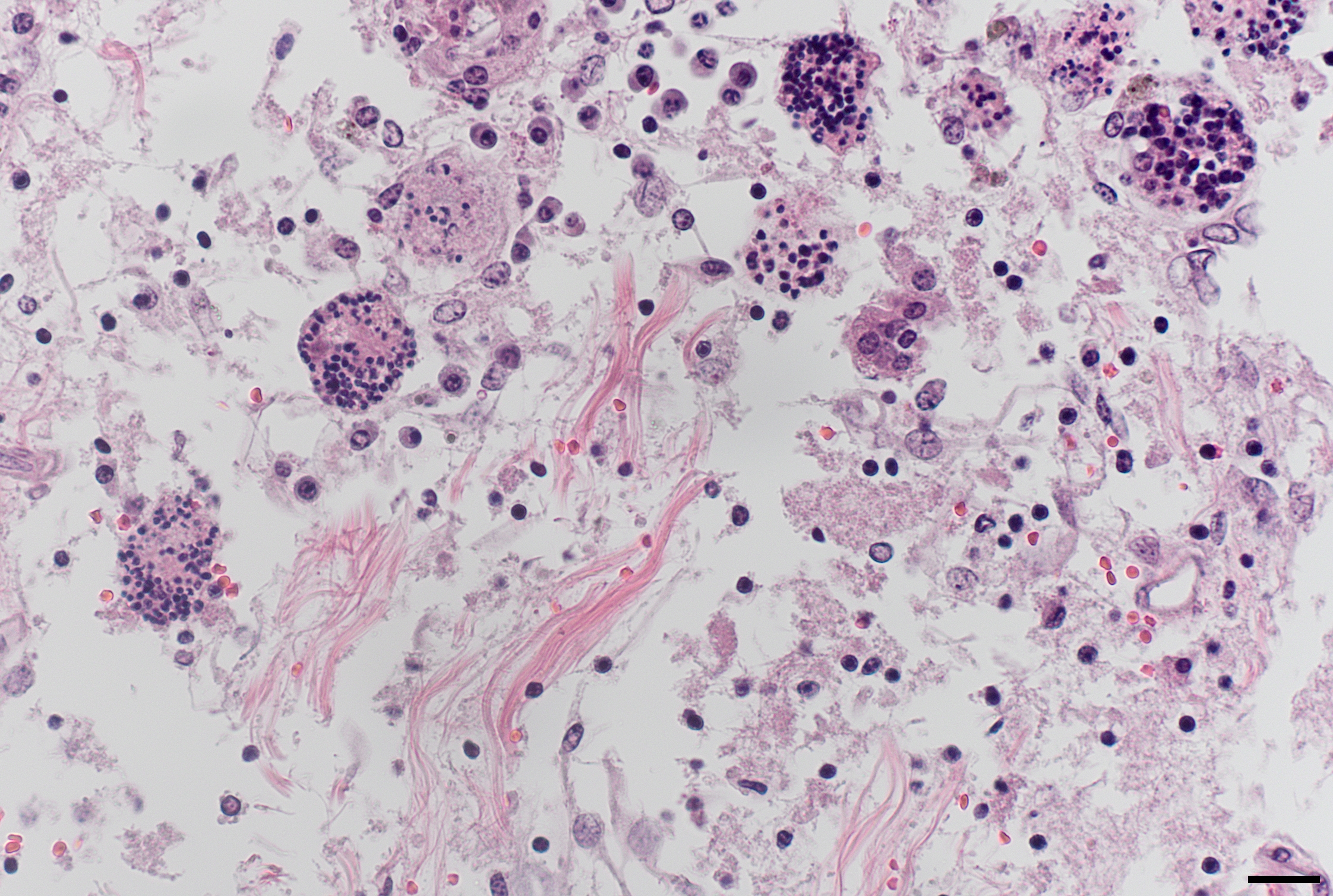

White-tailed deer ingest larvae, which migrate through the digestive tract via spinal nerves to reach the spinal cord and the brain. There larvae develop into adults, reproduce, and lay eggs within deer. Eggs hatch and travel via the bloodstream to the lungs. Deer get a tickle in their throat, cough up the larvae, swallow them, and they go out the back of the deer into the world.

These new larvae deposited into the world in an M&M-sized poop pellet are actually not infectious. For that, P. tenuis needs a hand or, in this case, a foot. The larvae must penetrate the foot of a snail noshing on those P. tenuis-flavored fecal M&Ms. There they mature to another larval stage. At last, they are ready to infect again!

Deer going about their daily business snack on a snail and get that little extra just like when they vacuum up those plant dwelling insects…and the cycle starts all over again.

What happens to deer infected with P. tenuis? Nothing! P. tenuis lives and breeds in the meninges. As a refresher, meninges are the 3 layers of membranes that protect the brain and spinal cord. Conditions like meningitis, an infection of the meninges caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites, are incredibly serious and can cause death if untreated. Yet white-tailed deer walk around like it’s no big deal. Other than that irritating cough to get the larvae through the system, deer don’t even notice or show any sign of disease.

P. tenuis is common almost everywhere white-tailed deer are found in eastern North America. About 80% of deer are infected with little to no disease seen.

That, however, is not the case for other hooved mammals. Moose, mule deer, black-tailed deer, elk, caribou, pronghorns, and big-horned sheep are all susceptible. So are llamas, sheep, goats, and alpacas. Unfortunately for all these critters, the blissful relationship enjoyed by white-tailed deer and P. tenuis is not replicated. If they swallow one of those seeded snails, worms won’t mature into reproductive adults. Instead, they just wander around the brain and spinal cord damaging meninges like some irate drunkard that is refused another round. The result is severe neurological disease and death.

For these critters, living in the same area as white-tailed is dangerous. Every year, some poor Pennsylvania elk snacks on the wrong snail and meets its demise.

In fact, P. tenuis is contributing to moose population declines in areas of North America. It’s like living next door to Clark W. Griswold. Your hapless neighbor is creating a vortex of doom completely oblivious to the destruction they are causing.

And the Griswolds are on the move pooping out larvae for snails to find. White-tailed deer are expanding their range into areas where endangered woodland caribou live. If the wolves that follow the deer don’t get the caribou, the larvae-infected snails might!

Clark Griswold means well. He’s just got a lot of baggage. The same is true for our beloved white-tailed deer.

-Jeannine Fleegle

Wildlife Biologist

PA Game Commission

*If you are a first-time commenter on the blog, your post will not appear until it has been approved by the moderator. This is to prevent spam overwhelming us. If you do not see your post within 24 hours, please email us at deerforeststudy@gmail.com