We estimate and use probabilities every day but when it comes to deer in the woods, those tools are rejected as hocus-pocus. In the quest to vanquish the estimation part of population estimates, some have turned to advancements in technology.

I mean, why not? Technology has given us GPS collars to follow the life and times of buck 8917 and DNA mapping to bust the myth of twins. Surely technology can put an end to estimating wildlife populations. Like some sort of X-ray vision we could use to see through the forest.

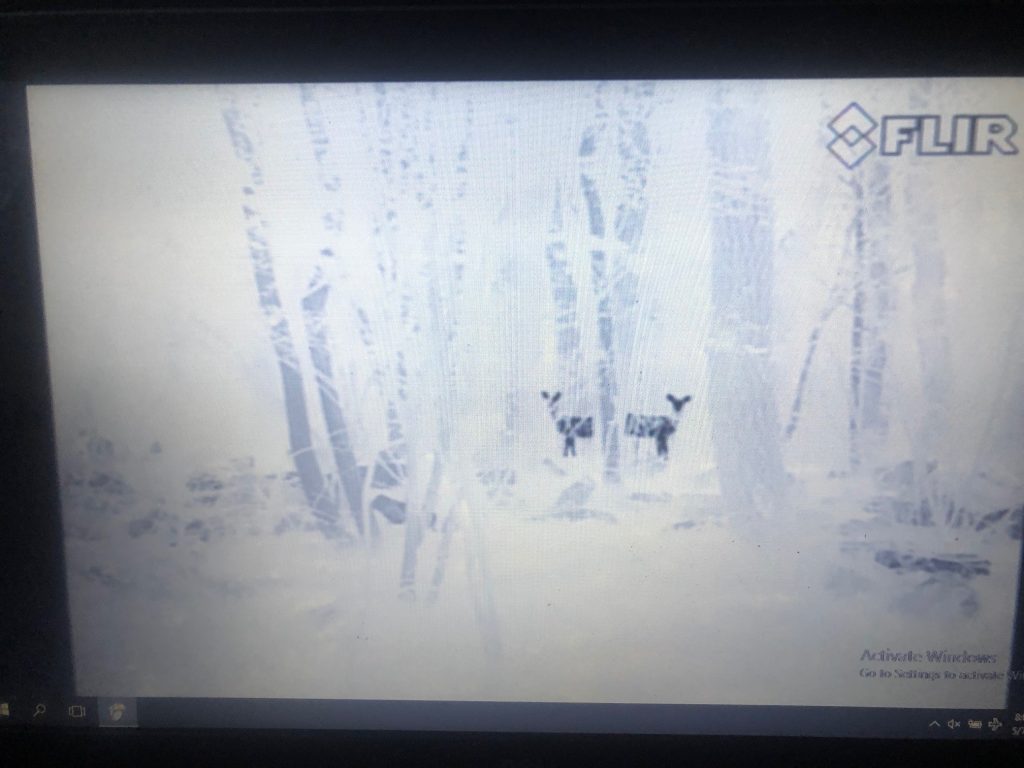

The science equivalent of X-ray vision is thermal imaging using forward looking infrared (FLIR) technology. FLIR uses infrared sensors to convert infrared radiation into the visible spectrum which improves the ability to detect things that are warmer than the surrounding environment and thereby removing their cloak of invisibility. Instead of undetectable apparitions, deer become glowing beacons in the night. Slap that fancy FLIR camera to a plane and take to the night skies! No deer can hide now. Right?

Wrong. Deer may be smoldering on the landscape but unless you can cover the ENTIRE area to be surveyed and deer don’t move while you’re doing it, FLIR is not going to get a complete count.

To throw population estimates out the window, you need a complete count which means ALL critters within the area in question. A FLIR transect is 150m wide. If we wanted to cover the smallest study area in the Deer-Forest Study (25 square miles), it would take 270 1-mile long transects or 135 2-mile long transects to fly over the entire study area. And then there’s our highly mobile subjects. Deer may be glowing all warm and fuzzy but they also are moving like Pacman gobbling dots across a TV screen.

And I haven’t even mentioned the 10th player in this game – habitat. The type of habitat affects the ability to detect those warm and fuzzy deer. As you might expect, open and sparsely vegetated areas and deciduous forests in winter were the best while dense conifers were the worst for deer detection. One study estimated that surveys using FLIR missed 11-69% of deer and concluded that “Until the capabilities of thermal imaging are more fully understood and the sampling protocols refined, detection rates may be too variable to provide reliable counts of animal abundance.”

But sometimes you have to learn things for yourself. In 2005, a group decided to use FLIR to count the deer in Blue Knob State Park. Eighty-six deer were counted with a 70% detection rate. At the same time, a spotlight survey was also conducted. Ninety-seven deer were counted with a spotlight.

Umm… you might want to read those last three sentences again – they counted more deer with spotlights than FLIR technology.

The moral of this story – FLIR technology will not vanquish the need for population estimates. It is another tool that can be applied to the many other population estimation techniques that already exist. For example, we are working to use FLIR as part of distance sampling along roads to estimate deer populations on The Deer-Forest Study.

FLIR definitely gives us the ability to see deer we otherwise would miss, but it does not give us that warm and fuzzy feeling of seeing EVERY deer.

-Duane Diefenbach and Jeannine Fleegle

If you would like to receive email alerts of new blog posts, subscribe here.

And Follow us on Twitter @WTDresearch

This post is part of a series on Population Estimation

Warm and Fuzzy (you are here)